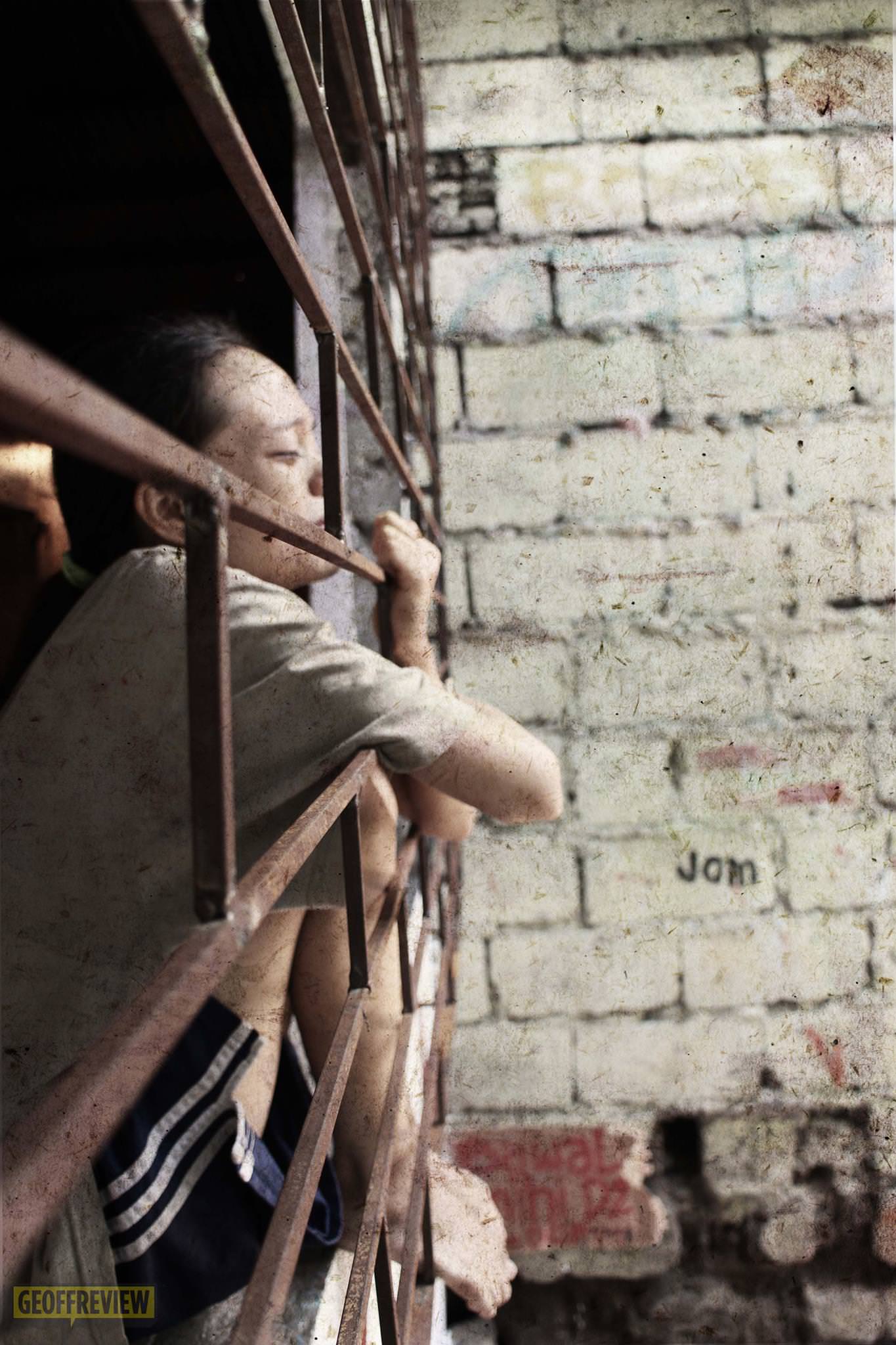

We entered the worn-down Barangay Multi-Purpose Hall with warnings not to offer the “clients” food, water, and most especially cigarettes. Each step was taken with uneasiness, knowing that the grimy men huddled against the walls and laying carelessly on filthy plywoods could jump at you anytime if they suddenly have an episode. The summer heat and humid air made it worse. The buzzing of flies also added to my discomfort, knowing that there are literally pieces of shit on one far corner of the room.

The “transient home” that we entered, was part of The UP Repertory Company ’s presentation of Walang Katapusang Godot – an 8-hour play directed by Manuel Mesina III, and based on Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and its Filipino adaptation by Rolando Tinio. Having witnessed the dreadful yet piteous predicament of the mentally-ill patients at the Fabella Transient Home in Mandaluyong, Mesina juxtaposed the seemingly endless waiting of the patients for their relatives, with the repetitive and ceremonial waiting of the characters in Beckett’s play.

A few hours after immersing ourselves into the transient home, one of the clients called out to us asking for Zest-O and Spanish Bread. We reluctantly answered no, taken aback by the fact that the actors are talking to us. I guess that’s how Museum Theater works – with the audience engaging with the interpreters, making us feel like we are a part of the production.

We started questioning the other visitors who entered with us – could they be a part of the production as well? Would there be some sick twist at the end of the play, revealing that my buddy and I are the only visitors, and everyone else around us are patients? (This thought gave me major vibes of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether”). At some point, we jokingly asked ourselves, what if we are also patients, and we just didn’t know it? After all, crazy people don’t know that they are crazy.

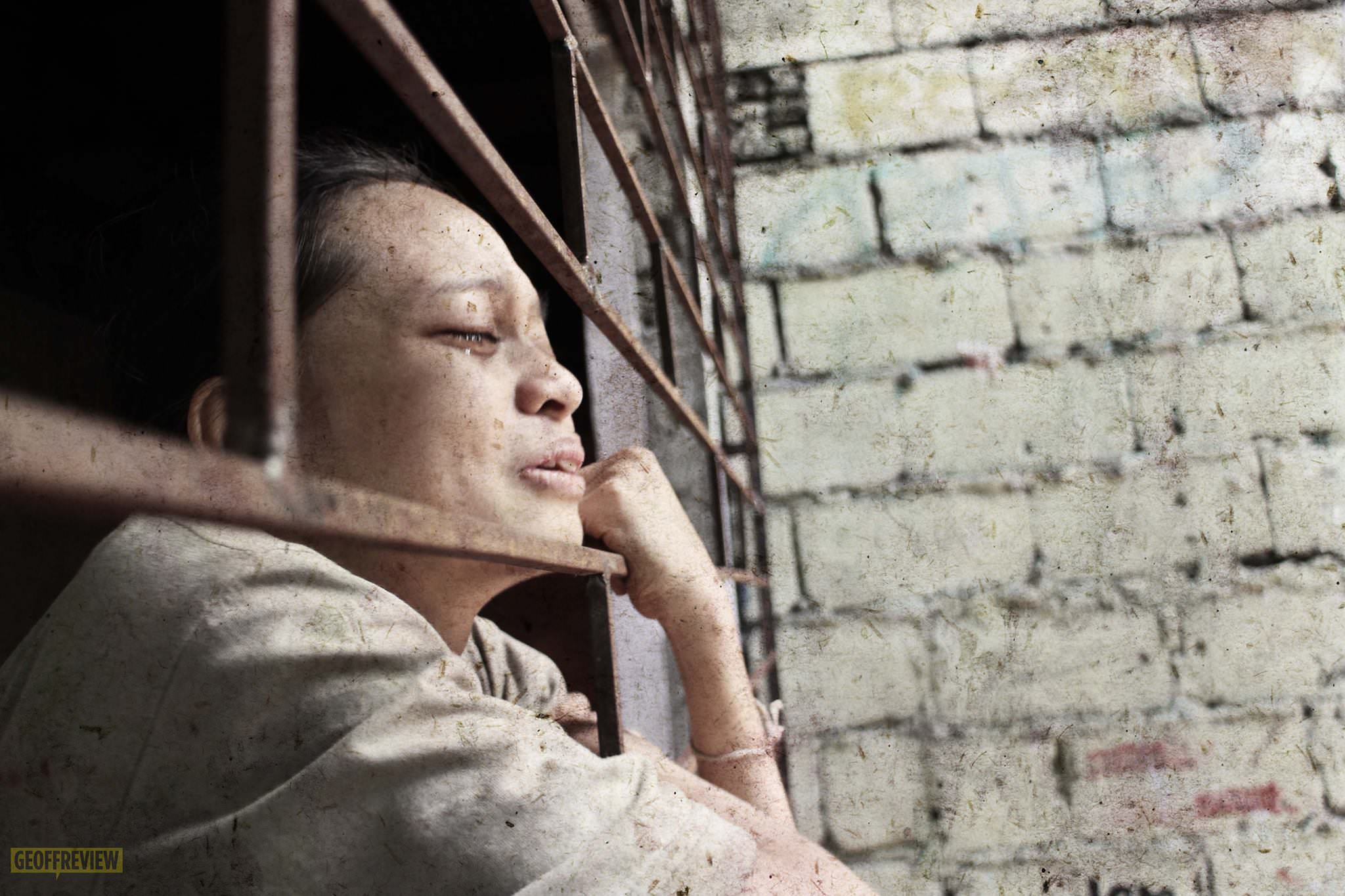

Walang Katapusang Godot is more than shock value and a test of endurance; it’s a peek into the socio-political placement of the mentally-ill in a capitalist society. Since they are not contributing to production, they have been regarded as useless and a burden. Set aside, endlessly waiting for redemption that never arrives.

As my friend asked me during the play, who are the real monsters here? Those who are feared because they are unstable, or those who left them behind?